Referral Notes:

- Current indoor navigation aids for those with visual impairments are often costly, complex, and require added infrastructure; most people who are blind or have low vision still rely on human guides to navigate new spaces.

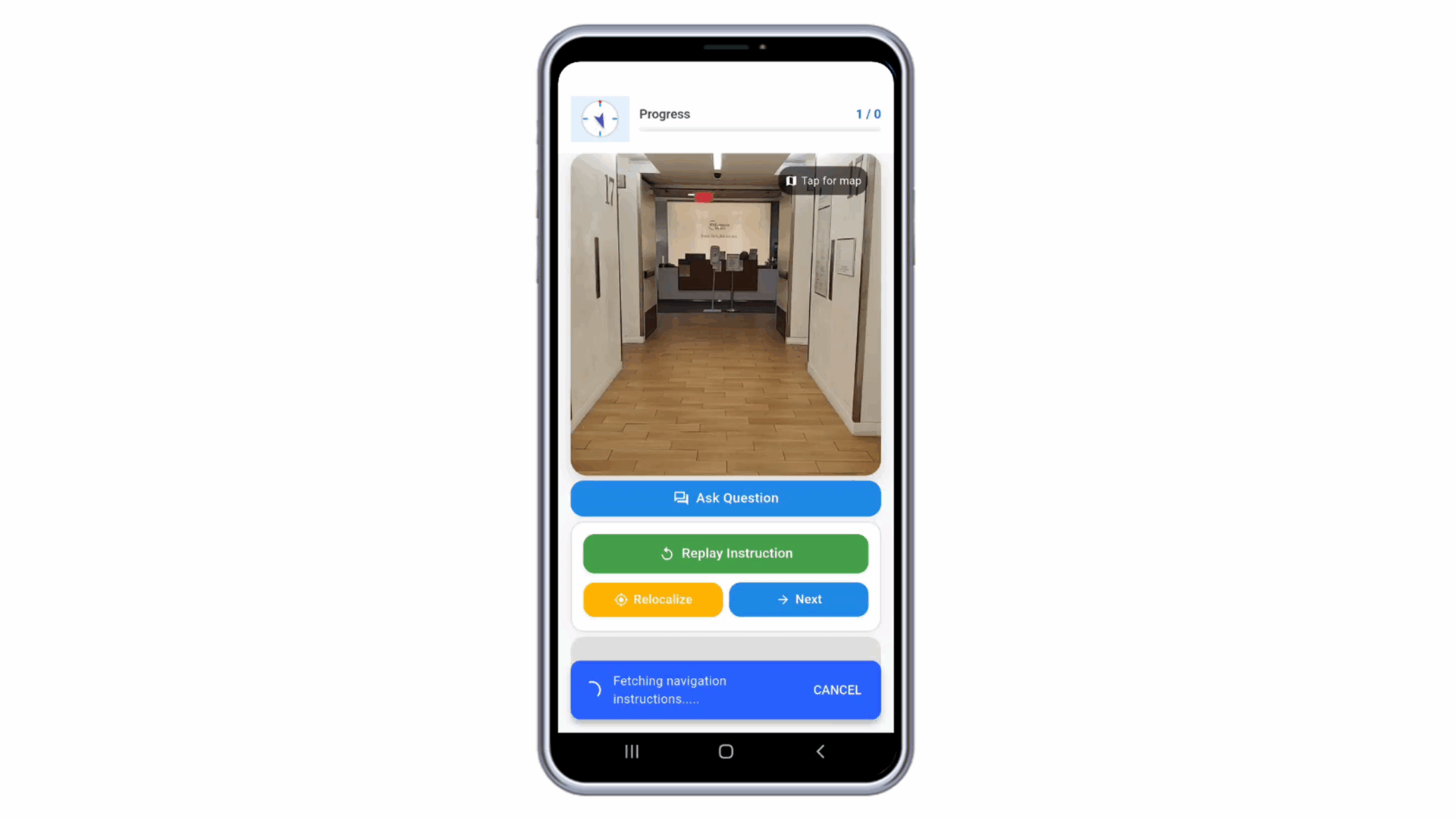

- The UNav smartphone application can guide users, step-by-step, through both indoor and outdoor spaces.

- In an international study with 20 persons with blindness or low vision, UNav outperformed in-person travel directions in terms of pathing efficiency, travel time, wrong turns, stop periods, cane contacts, and more.

- By enabling precise, low-cost navigation for persons with visual impairment, UNav could expand access to education, work, and recreation.

A team from NYU Langone Health and the NYU Tandon School of Engineering has developed UNav, an easy-to-use smartphone application, that uses computer vision to help localize and navigate people who are blind or have low vision independently through unfamiliar spaces—delivering step-by-step walking instructions both indoors and outdoors, all without needing a guide or any pre-installed sensor infrastructure.

Developed with support from a $5 million grant from National Science Foundation, a clinical trial demonstrated that UNav was not only non-inferior to standard in-person travel directions, but was instead statistically superior for eight of the nine performance metrics evaluated, including improved pathing efficiency, reduced total travel time as well as reducing the amount of wrong turns made, requests for assistance, or cane contacts with obstacles.

Study senior author John-Ross Rizzo, MD, the Ilse Melamid Associate Professor of Rehabilitation Medicine and director of NYU Langone’s Rehabilitation Engineering Alliance and Center Transforming Low Vision (REACTIV) laboratory, says the technology could make it easier for those with visual impairments to access environments for work, education, healthcare, and recreation.

How It Works

To support an area for UNav, a lightweight 3D digital model of the environment is made in advance. This involves combining a floorplan with the visual features found in the environment that have been extracted from a single video walkthrough.

When a user enters the new environment, the UNav smartphone application will prompt them to select a destination (via speech or menu) and take a photo of the environment. This image is anonymized and sent to the UNav server, where its computer-vision method identifies any distinctive visual features. By matching these features to the 3D map, UNav can determine the user’s location and orientation, calculate an optimal route to their destination, and deliver step-by-step wayfinding instructions through verbal and haptic feedback.

“One of the mottos in our lab is whatever we create must work without any physical infrastructure, just digital.”

John-Ross Rizzo, MD

The UNav project started almost a decade ago and is especially important to Dr. Rizzo, who has the inherited, progressive eye disorder, choroideremia. “The barriers are significant for people with a vision impairment,” he says

The technology was designed to address the limitations of existing navigation aids, including high cost, limited availability, extensive infrastructure requirements, training burden, and poor ergonomics. As a result, those with visual impairments primary rely on human guides to navigate new environments.

“We wanted to create more frictionless experiences and a better product,” says Dr. Rizzo, who is also an associate professor of biomedical engineering at NYU Tandon School of Engineering and associate director of NYU WIRELESS, a 6G wireless research center. “One of the mottos in our lab is whatever we create must work without any physical infrastructure, just digital.”

Putting the Tech to the Test

To evaluate UNav in a real-world setting, 20 participants with varying levels of visual impairment, ages 23 to 54, were asked to navigate short routes using either UNav or standard in-person travel directions from a trained human guide.

Participants were people living in and around Bangkok, and the routes were selected from buildings and outdoor spaces on the Mahidol University campus, where 3D maps had been generated in advance. Routes ranged from 50 to 200 meters and included two to four turns. Each participant completed every route twice, once with UNav and once with in-person travel directions, with order randomized to control for route familiarity.

“UNav isn’t just about navigation, it’s about societal access.”

Compared with in-person travel directions, UNav use was associated with shorter, more efficient pathing, fewer wrong turns, fewer cane contacts with walls and obstacles, reduced idle time, and faster route completion time. UNav users also made less requests for assistance.

“UNav isn’t just about navigation, it’s about societal access,” says Dr. Rizzo. Persons with visual impairments experience higher unemployment, reduced access to healthcare, lower bachelor-degree attainment, and tend to have fewer in-person social interactions. “By increasing independence and confidence in navigation, we aim to make employment, healthcare, education, and social opportunities more accessible for people with visual impairments,” he says.

Looking Ahead

Ongoing work aims to further improve UNav’s utility with live-tracking journey progression through the smartphone’s motion sensors, and adding an optional AI “running commentary” that live-describes what is happening in the environment.

Work has also begun on more commercially orientated versions of the UNav application, with the goal of aiding navigation in universities, hospitals, airports, sports arenas, malls, and large transit stations for everyone. “We’re inching closer every day,” Dr. Rizzo says. “I can’t wait for the day we have this fully deployed and positioned in a commercial entity.”

The UNav platform also supports emerging navigation applications, including robotics and assistive technologies, making it adaptable to future innovations. “We want this technology to scale in a simple and efficient manner,” Dr. Rizzo says. “NYU has been a great ecosystem to do this work.”

His team plans to lead additional clinical trials to further evaluate UNav’s effectiveness and real-world impact.