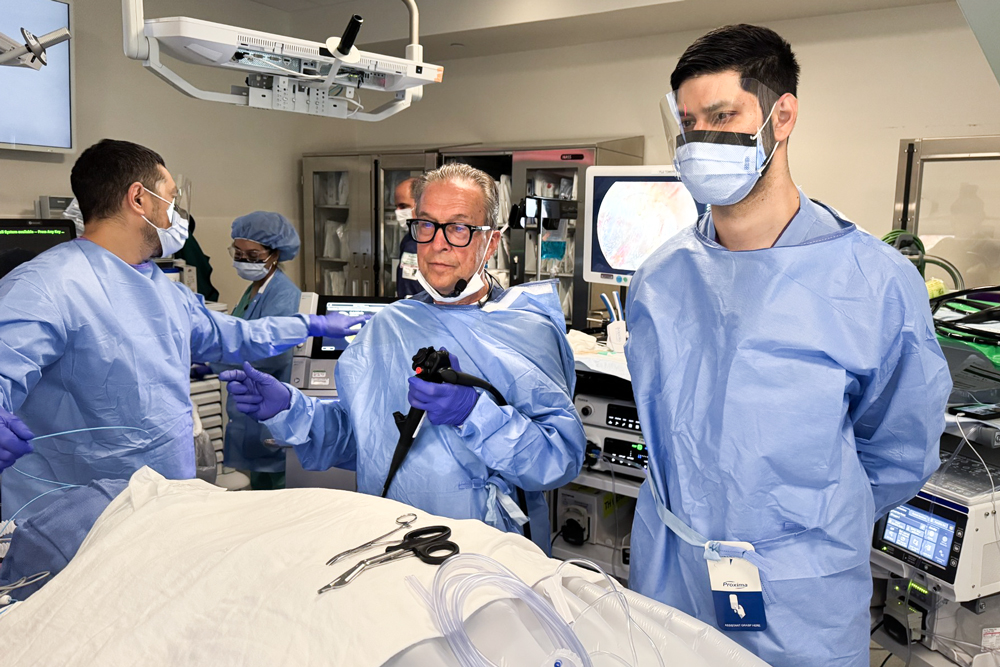

Gregory B. Haber, MD, chief of endoscopy at NYU Langone Health and an international leader in therapeutic endoscopy, has been honored with the 2025 Rudolph V. Schindler Award—the highest distinction granted by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE). This prestigious lifetime achievement award is presented annually to a member whose contributions have profoundly advanced the science and practice of GI endoscopy.

Dr. Haber has trained more than 100 fellows, introduced breakthrough endoscopic techniques, and helped redefine what’s possible in minimally invasive GI care. In this conversation, Dr. Haber reflects on the mentors and milestones that have defined his remarkable career.

Physician Focus: As you look back, what career highlights shaped your path to this recognition from the ASGE?

Dr. Haber: I’ve attended these award ceremonies for years; to now be among the honorees feels surreal. But no one gets here alone. This recognition reflects the work of many mentors, collaborators, and trainees.

One early turning point was during my postgraduate research in England. I had received a Medical Research Council of Canada grant to study bile acid metabolism with Dr. Ken Heaton at the Bristol Royal Infirmary. While there, I had the good fortune to attend endoscopy sessions with Dr. Paul Salmon, then president of the British Society of Gastroenterology. That experience ignited my passion for advanced endoscopic procedures and shifted my entire career focus.

“I’ve learned as much from international colleagues while teaching around the world as I did during formal training.”

Gregory B. Haber, MD

On returning to Toronto, I joined the therapeutic endoscopy team of Dr. Norman Marcon at the University of Toronto. Canada’s socialized medicine system resulted in referrals from across the province to our center, where performing 30 to 35 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures per week was routine. It provided me with the volume—and the associated challenges—needed to master my craft.

In the second half of my career, I traveled to meetings in Asia, where our Japanese colleagues were refining techniques in endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for cancerous lesions of the GI tract. From hours spent observing those procedures I was able to begin my focus in third-space work—procedures that have proven to be game changers for patient quality of life.

Of course, as one becomes an expert in one area, you become a teaching resource for others, which opens even more opportunities for growth. Serving as faculty at national and international meetings, I learned from exceptional colleagues presenting advances in endoscopy. I’ve learned as much from international colleagues while I was teaching around the world as I did during formal training.

Physician Focus: What innovations or techniques are you most proud to have contributed to, and why?

Dr. Haber: Removing bile duct stones without surgery—what we now do routinely with ERCP—was revolutionary when I first introduced it in Canada. I later brought those procedures with me to New York, where I also introduced techniques like double-balloon enteroscopy and endoscopic treatment for Zenker’s diverticulum. I honed these techniques through my travels and teaching across the globe.

About 80 percent of the procedures that would have required open surgery at the beginning of my career are now performed endoscopically. All along, my focus has been to adapt to new techniques with the greatest benefit to patients—always exploring what diseases we could be treating endoscopically for better outcomes.

Physician Focus: What have you learned from training the next generation of physicians that has helped you become a better mentor?

Dr. Haber: I’ve been privileged to train fellows from around the world. Each trainee brings a unique perspective shaped by their own medical system and hands-on experiences. For example, in some settings where access to expensive instruments is limited, fellows have demonstrated how to use something as simple as a dental elastic band to replicate what a $10,000 robotic traction device might do in endoscopic dissection. That kind of resourcefulness teaches you never to underestimate ingenuity.

Training is also a two-way street. Fellows ask questions that challenge us to rethink accepted conventions.

“Never assume a trainee knows everything leading up to the skill you’re teaching. Effective mentorship means tailoring your approach to each learner.”

I’ve also learned to never assume a trainee knows everything leading up to the skill you’re teaching. Effective mentorship means tailoring your approach to each learner, recognizing their stage in the learning process. It’s made me not only a better mentor but also a better physician.

Physician Focus: What advice do you give to young gastroenterologists entering the field today?

Dr. Haber: First, find what truly drives you, whether it’s clinical care, procedural expertise, or research. If you choose advanced endoscopy, understand that experience is everything. Watch experts. Seek mentorship. And be patient with yourself—skills take time to build. Some fellows arrive with 80 percent of the requisite skill set for a procedure and just need refinement. Others are novices and need guidance in the basics to build from the ground up. Either way, perseverance matters.

Physician Focus: How do you see the field of interventional endoscopy changing over the next 5 to 10 years, and how might physicians prepare now for those changes?

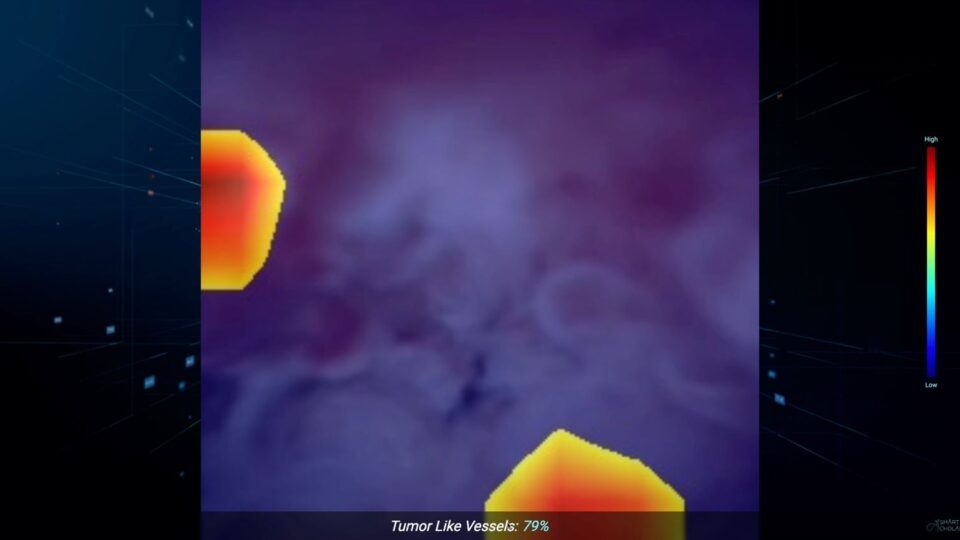

Dr. Haber: Driven by the abundance of digital tools, the rate of learning has accelerated dramatically. We can access information on any disease or technique in seconds. But the challenge remains: How do you apply what you’ve read or watched? The only way to gain true expertise is by treating patients—understanding the specific needs of each disease and refining the endoscopic skills to use these technologies effectively.

Over the next decade, that fundamental truth won’t change. Yes, robotics, AI, and other advances will continue to enhance safety and precision, but you still have to learn how to run the robot and apply the abundance of resources. Technology must be applied appropriately, where it truly improves outcomes for each individual patient. It’s not just mastering technology, it is understanding the disease and what achieves the best outcome.