Methotrexate, the first-line medication for rheumatoid arthritis, works as a monotherapy in only about 50 percent of patients, necessitating a trial and error approach to find the right combination of medications for each patient.

If methotrexate fails to control a patient’s rheumatoid arthritis after three months, as a general rule of thumb, clinicians try a different strategy. “That’s a critical amount of time during which someone’s disease is potentially progressing and becoming more destructive,” says rheumatologist Rebecca B. Blank, MD, PhD.

“One of our thoughts was, can we shift this microbiome toward microbes that don’t break down methotrexate as much?”

Rebecca B. Blank, MD, PhD

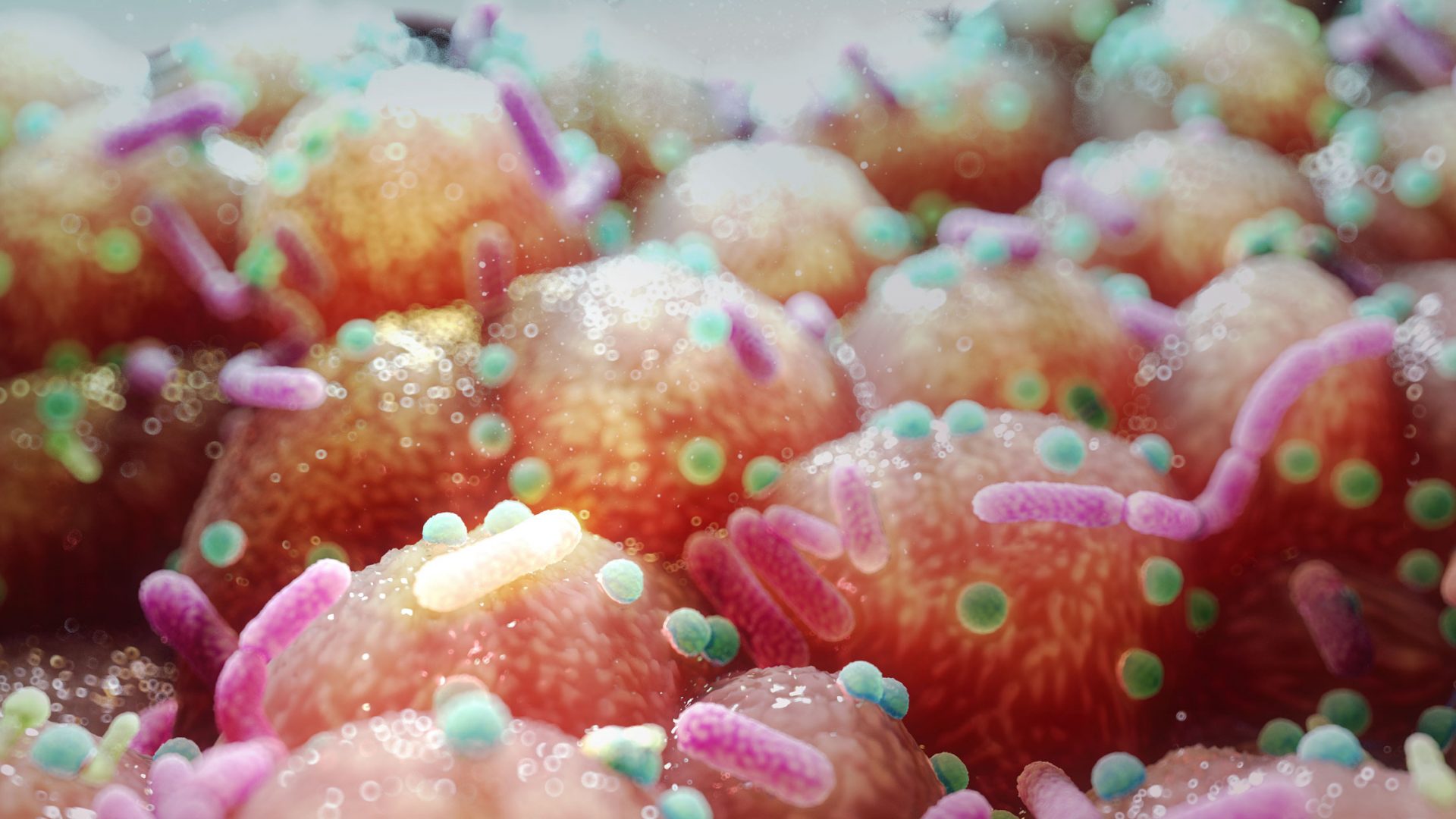

Supported in part by NYU Langone Health’s Clinical and Translational Science Awards Scholars Program, Dr. Blank is exploring whether differences in the gut microbiome may help predict the responsiveness of a patient’s rheumatoid arthritis to methotrexate. In addition, she’s assessing whether strategic alterations to the microbiome might enhance the medication’s effect.

A Consequential Microbial Shift

Prior research led by rheumatologist Jose U. Scher, MD, director of NYU Langone’s Microbiome Center for Rheumatology and Autoimmunity, found that certain gut microbial DNA signatures predict methotrexate responsiveness. From those results, Dr. Blank and Dr. Scher hypothesized that some gut microbes may be metabolizing methotrexate into metabolites and preventing the drug from reaching a patient’s joints.

“One of our thoughts was, can we shift this microbiome toward microbes that don’t break down methotrexate as much?” Dr. Blank says.

Another question is whether the microbiome could be pushed into a more immunoregulatory state, one that reduces the “leaky gut” phenomenon that can spur inflammation.

Based on data from animal studies of rheumatoid arthritis and from clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease and pediatric obesity, Dr. Blank narrowed her focus to microbes that produce short-chain fatty acids as their fermentation products.

These bacterial products have been shown to ameliorate inflammatory arthritis in mice by reducing inflammation at the joint and decreasing inflammatory T helper 17 cells while increasing systemic regulatory T cells. One short-chain fatty acid, butyrate, seems to have the most significant effect. In humans, some evidence suggests that butyrate supplements yield a positive feedback loop that shifts the gut toward more butyrate-producing microbes.

A New Focus on Butyrate

Combined, the findings point toward the possibility that supplementing methotrexate with butyrate in patients with new-onset rheumatoid arthritis might shift the gut microbiome toward a state of reduced inflammation and even decreased methotrexate metabolism, helping to explain the microbial signature predicting methotrexate responsiveness.

In a pilot trial involving 16 patients newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and receiving methotrexate, Dr. Blank and colleagues are testing just this question. As part of the study, the researchers aim to determine whether butyrate supplementation correlates with an increase in T regulatory cells and a decrease in inflammatory T cells, like the shift seen in mice. In addition, the research could reveal the role of butyrate producers in the methotrexate response signature.

“If butyrate does have an impact on the microbiome and an impact on downregulating inflammatory responses systemically, it could be an adjunct to a number of different rheumatoid arthritis medications.”

So far, gut microbiome analyses from eight of the patients have revealed lower microbial alpha diversity than healthy controls at baseline. After four months of butyrate supplementation, however, their microbiomes are showing significant shifts toward higher alpha diversity, compared with historical controls of rheumatoid arthritis patients given methotrexate alone.

In particular, Dr. Blank and colleagues found a relative increase in the bacterial taxa known to produce short-chain fatty acids like butyrate.

“I think what’s happening is that you’re creating more diversity of microbes, which then out-compete some of these other microbes that are metabolizing the methotrexate into inactive products,” she says. “You’re essentially pushing the pathogenic microbes out of the way.”

Testing a Potential Adjunct Therapy

Supported by a grant from the Arthritis Foundation, Dr. Blank is expanding her focus with a small pilot study on patients whose first-line methotrexate therapy is starting to fail.

Before switching the patients to a new regimen, she’s assessing whether butyrate supplementation and a corresponding shift in the gut microbiome might prolong methotrexate’s efficacy.

If her pilot trials yield promising results, Dr. Blank hopes to partner with other academic centers on a placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess the benefits of supplementing methotrexate with butyrate. “If butyrate does have an impact on the microbiome and an impact on downregulating inflammatory responses systemically,” she says, “it could be an adjunct to a number of different rheumatoid arthritis medications.”