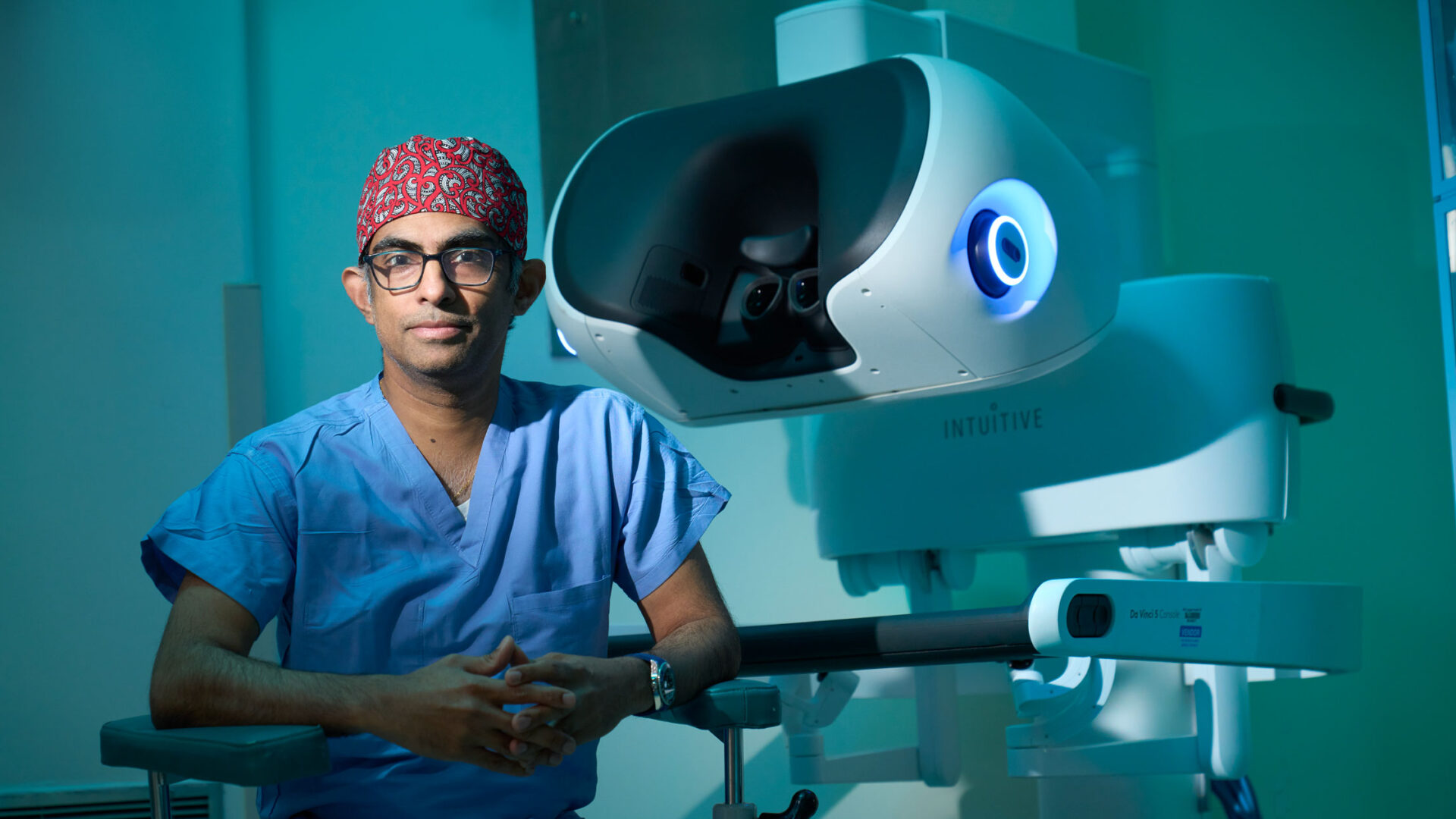

Umamaheswar Duvvuri, MD, PhD, sat down with Marc K. Siegel, MD, at Doctor Radio on Sirius XM to discuss his pioneering work on robotic surgery, running the Department of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, and where the future lies in his field. Subscribers can hear the full conversation; the interview extract below has been edited for length and clarity.

Dr. Siegel: Tell me about your background. How did you get to where you are now?

Dr. Duvvuri: I was born in India, in a city called Hyderabad, in the south of India. When I was seven, my dad decided he wanted a new experience, so he moved us to Jamaica. Not Jamaica, Queens, but the country, the island. So, I grew up in the Caribbean, and when I finished high school, I was lucky enough to get accepted to UPenn.

My bachelor’s is actually in biomedical engineering, and one of the people that I worked with was a scientist who did a lot of work on imaging and how engineering affects medicine and biomedical engineering.

I asked him to write me a letter of recommendation to be a graduate student, because I wanted to be a PhD, just like him. He looked at me, he said, no. And I said, why not? And he said, there are three kinds of people in this world. The ones that have the hammers, that’s the engineers. The ones that have the nails and know what the problems are, those are the doctors. There’s a small third group of people who know both. What do you want to do? So, if you put it that way, well, I want to be the third group that knows both. And he said, that’s right. So you’ve got to be an MD PhD.

I was born in India. When I was seven, my dad decided he wanted a new experience, so he moved us to Jamaica. So, I grew up in the Caribbean.

Umamaheswar Duvvuri, MD, PhD

At that time, I knew I wanted to do something that involved working with my hands, where I helped people, where I saw immediate gratification from taking care of patients. Surgery was a clear link to that. And because of my background, coming from India, head and neck cancer actually struck me as being particularly relevant. I’ve had family members with it, and it’s actually one of the leading causes of death in the world in terms of cancer.

And so, I decided to become an otolaryngologist to take care of patients with head and neck cancer. That was my motivation, with the intention of hopefully one day being able to contribute back to India.

Dr. Siegel: Talk to me a little more about robotic neck dissections, which is part of what you’ve pioneered. How exactly are they performed using a robot?

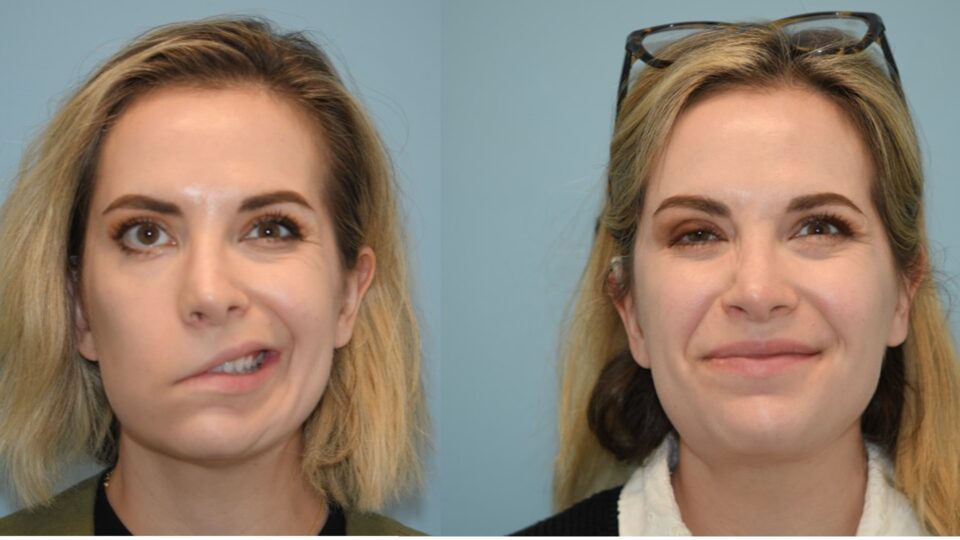

Dr. Duvvuri: We do it usually with an open approach, where you make an incision that starts just around the back of the neck, under the ear, and comes across towards the voice box. It’s about a 3- to 3.5-inch incision, which is quite large but can be hidden very nicely, and can be very cosmetic and closed well. But when you cut across those lymphatics in the neck, you always develop some amount of lymphedema. And the patients often complain that they have what they call turkey gobble under their chin.

To avoid that, we developed a technique that uses a modified facelift approach which displaces that scar, putting it in a place in the hairline. When you lift up the skin, you put the surgical robot under that skin incision, and you use that to remove the lymph nodes. Same operation, just done a slightly different way.

Not only is there benefit from cosmesis, there’s also benefit from the functional outcomes, because when you save all that skin and you prevent those scars, you get a lot less edema in the neck after surgery. That’s really beneficial to the patients, supporting good oncologic outcomes.

We just published our five-year outcomes on this. We showed that if you compare patients who had robotic neck dissections versus patients that had traditional neck dissections, their five-year overall survival was the same. So, this is not an inferior technique in terms of survival, and it improves blood loss and improves outcomes.

Dr. Siegel: When will you be able to operate in other places of the world using the robotic console?

Dr. Duvvuri: It’s a very interesting question. I just came back from a big meeting from the Society of Robotic Surgery, where we discussed this. It turns out that surgeons in China have been doing this for the last year, and they’ve actually been operating about a thousand miles away from each other. They can do surgeries across the different coasts of China. The technology is here. The delays in what we call latency have been solved. They can be controlled.

“It turns out that surgeons in China have been doing [telesurgery] for the last year, and they’ve actually been operating about a thousand miles away from each other.”

The problem for America is we have a very high bar for safety. The ability to actually go through all the regulatory framework is honestly our biggest holdup. We want to make sure that we’re doing things in a safe and careful fashion. But the technique, the technology, the ability, it’s actually here.

So, I don’t think that this is too far away. And this is actually one of the things that I’m passionate about, is bringing telesurgery or telemedicine truly to our space, because I strongly feel that just because you happen to live in a smaller town or a smaller city doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t have access to the same quality of care that you might get anywhere else.

Dr. Siegel: The issue of thyroid-sparing surgery appeals to me, because if I’m treating somebody that had a partial thyroidectomy versus a total thyroidectomy, it’s a different clinical appearance—how much thyroid hormone I have to use, how much I have to worry about things. Does the robot help you spare thyroid tissue?

Dr. Duvvuri: The short answer is no. The robot itself doesn’t help us. But I think what the robotic techniques have allowed us to do is to do the surgery in a very safe fashion and allowed us actually to incorporate modern advances to be more precise about making sure the tumors are removed.

The American Thyroid Association has now told us, based on lots of data, that a partial thyroidectomy is a safe operation for people that have small thyroid cancers, those that are confined to the thyroid and haven’t spread to lymph nodes. You can do that safely, especially at a place like NYU Langone Health, where we have a tremendous team of endocrinologists and surgeons that work together. We can really work to create a personalized treatment plan to give the patients the right type of treatment.

When I was a young doctor, if you had a thyroid cancer, the whole thyroid was coming out, and you were going to get radioactive iodine. Now, not so much. We can use molecular testing. We can use genetic algorithms. We can use technologies like radiofrequency ablation. We can do lots of things to minimize the toxicity profile for our patients.

Dr. Siegel: You use both robotic and nonrobotic approaches. Which head and neck procedures are more prone to needing one versus the other?

Dr. Duvvuri: It’s not as simple as that. It’s not that you’ve got tons of cancer, so you get a robotic surgery, or you got thyroid cancer, so you don’t. It’s much more an issue of, is the robotic approach or the open approach going to give the patient the best outcome and, ideally, with the least amount of toxicity so that they can carry on with their lives?

“The goal is not to have the treatment be worse than the disease in some sense. This is the approach that I would like us all to move towards as a field.”

The goal is not to have the treatment be worse than the disease in some sense. This is the approach that I would like us all to move towards as a field, and we do this here at NYU Langone, which is, how can we deescalate and appropriately personalize the care for these patients? The goal here is that, going back to the hammer-and-the-nail analogy, not every nail needs the same hammer.

Dr. Siegel: I left out something we’re really, really world-renowned for, which is cochlear implants. What about AI? How is AI going to be integrated into ENT here?

Dr. Duvvuri: Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms are definitely changing how we think about the delivery of care. There are a couple of ways that we’re looking at this. One is understanding, going back to this point, the right treatment for the right patient at the right time. Can artificial intelligence algorithms allow us to synthesize large amounts of data to figure out what’s happening?

I’m also very privileged to be a part of a clinical trial that just opened at our veterans hospital, where we’re using artificial intelligence to prognosticate how patients will do with algorithms for treatment for oropharyngeal cancer with chemotherapy and radiation. This is a huge study, it’s a multicenter study. And I think this highlights how AI and machine learning algorithms may have unexpected roles. I don’t think it’s going to replace a doctor or a surgeon anytime soon. But I do think it will augment how we make our decisions.