In recent years, microplastics have been found in places ranging from the upper atmosphere to deep ocean trenches, as well as in virtually every corner of the human body. Little is known, however, about the impact of these particles on physiological function or disease processes.

Here, Stacy Loeb, MD, a professor of urology and population health at NYU Langone Health, discusses a study she and her colleagues recently launched on the relationship between microplastics and prostate cancer. An internationally recognized expert on the relationship between environmental factors and urologic health, Dr. Loeb also highlights steps that can be taken on an individual and societal level to reduce or mitigate potentially harmful exposures.

Physician Focus: Dr. Loeb, what led you to investigate possible links between microplastics and prostate cancer?

Dr. Loeb: What got me interested in this topic was a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2024 showing that some people have microplastics in their carotid artery plaques—and that those who do have a more than fourfold greater risk of major cardiac complications than people whose plaques are plastic-free.

Soon afterward, a group of Turkish researchers published the first study demonstrating the presence of microplastics in prostate tissue. Those two papers made me wonder if microplastics might also be associated with prostate cancer, whose incidence in the U.S. has increased by three percent a year over the past decade.

“This stuff is so ubiquitous that it took months just to develop protocols to reduce contamination.”

Stacy Loeb, MD

Preclinical studies show links between microplastics and potentially carcinogenic processes such as DNA damage and oxidative stress. But much more research is needed to understand how they may fuel actual malignancies, whether in the prostate or other areas of the body.

Physician Focus: How are you looking into that question?

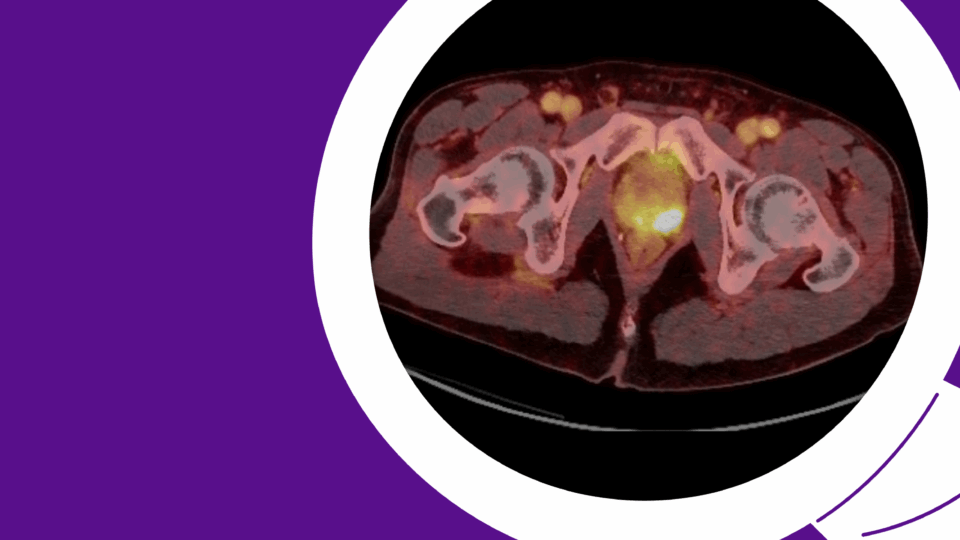

Dr. Loeb: We received a grant from the Department of Defense to look for microplastics in prostate tissue from 30 patients with prostate cancer. We’re examining samples from both the tumor and other areas of the prostate. The goal is to see whether the amount or types of plastic are different in cancerous and benign tissue.

To do that, we’re using Raman microspectroscopy and pyrolysis-GC-MS. The first technique enables us to visualize the plastic particles in each sample. The second allows us to quantify those particles.

One of our biggest challenges is the need to avoid incidental exposure of the samples to plastics. We normally use lots of plastic in the operating room during a prostatectomy, and in the labs where tissues are dissected and examined. For the study, we’re using alternative options wherever possible. This stuff is so ubiquitous that it took months just to develop protocols to reduce contamination.

Physician Focus: What are your preliminary findings?

Dr. Loeb: So far, we’ve run samples from 10 patients. In nine of them, we found microplastics in the prostate, and the concentrations were higher in the tumor than in the benign tissue outside of it.

“Even if we stopped producing plastic today, we’ll be dealing with its presence in the environment for centuries.”

Those results support our hypothesis, and they confirm the findings of a small study published recently by Chinese researchers. However, we need to look at many more cases before we can draw any firm conclusions. Based on our positive early results, we’ve applied for funding to expand our study beyond its current parameters.

Physician Focus: Is there anything we can do to protect people against the potential health impacts of microplastics?

Dr. Loeb: I don’t think we can eliminate exposure to these materials—they’re in the food we eat, the water we drink, the air we breathe. Even if we stopped producing plastic today, we’ll be dealing with its presence in the environment for centuries. But there may be ways to reduce exposure or mitigate its effects.

On an individual level, we can stop storing or heating foods in plastic containers and avoid single-use plastic bottles. On a societal level, we can implement global regulation of plastics, and accelerate the development of alternative materials. We need to ramp up research into alternative materials. And we need to investigate ways to protect our bodies against the impacts of plastic pollution, whether through diet, lifestyle changes, or other interventions.

We’re in the early stages of grappling with this problem, but I believe we can change things for the better.