Referral Notes:

- Sarcopenia of the pharyngeal muscles is a primary contributing factor in age-related dysphagia, yet little is known about how it can be prevented.

- A clinical trial led by NYU Langone Health researchers is investigating whether pharyngeal muscle exercises can preserve swallowing function in older adults, and whether protein supplementation can amplify that effect.

- Participants undergo a 12-week regimen of swallowing exercises, with or without daily protein drinks, while receiving periodic tests of pharyngeal strength and function.

- If the results are positive, the method could be used in clinical settings including community centers and senior living facilities.

Up to 22 percent of adults aged 60 or over will experience dysphagia, whose complications can include malnutrition, dehydration, aspiration pneumonia, and psychosocial impacts such as isolation and depression. Sarcopenia of the throat muscles is often cited as a primary contributing factor in age-related dysphagia, yet little is known about how it can be prevented.

A new clinical trial led by NYU Langone Health researchers aims to find answers to that question. Funded by the National Institute on Aging, the trial is investigating whether specialized muscle exercises can preserve swallowing function in older adults, and whether dietary changes can amplify that effect.

“In order to build muscle, protein synthesis must outweigh protein breakdown, and exercise and nutrition stimulate that process,” explains principal investigator Sonja M. Molfenter, PhD. “We hypothesize that deterioration of the swallowing muscles may reduce protein intake, creating a vicious circle—and that proactive interventions can keep that from happening.”

Building on Earlier Research

Sarcopenia of the swallowing muscles has been studied extensively in the tongue. Over the past decade, however, evidence has emerged that the pharyngeal muscles also play a central role in swallowing, and that they lose bulk with age. In previous research, Dr. Molfenter and colleagues established that such changes are associated with impaired swallowing biomechanics and function.

“We hypothesize that deterioration of the swallowing muscles may reduce protein intake, creating a vicious circle—and that proactive interventions can keep that from happening.”

Sonja M. Molfenter, PhD

This insight led the team to begin testing the ability of strength training and protein consumption to ward off pharyngeal sarcopenia. In a pilot study, they subjected five healthy older women to a daily regimen combining two components: swallowing exercises of the kind commonly used by speech–language pathologists to treat dysphagia, and consumption of commercially available protein drinks.

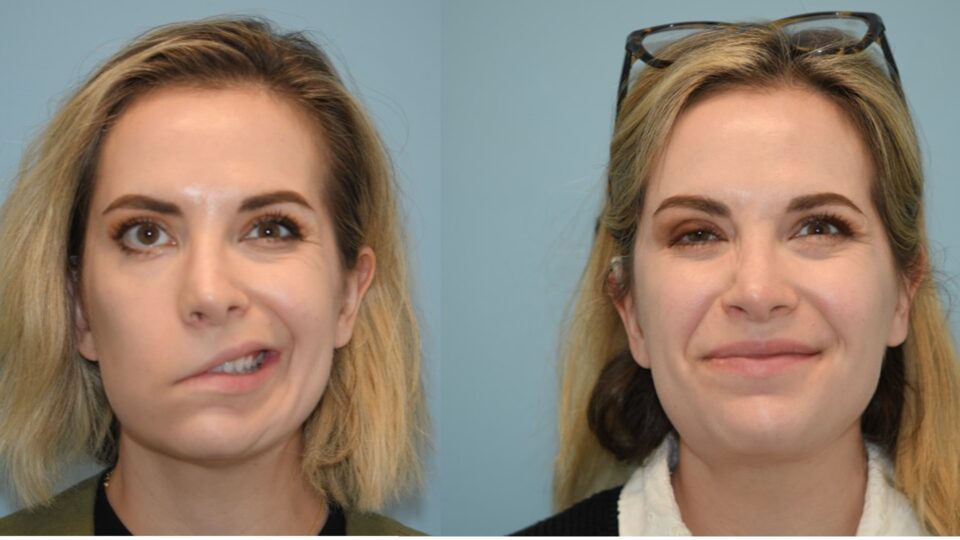

After eight weeks of treatment, four of the five participants showed improvements in measures including posterior pharyngeal wall thickness, passive swallowing strength, and maximum pharyngeal constriction. Encouraged by these early results, the researchers began what they envisioned as a full-scale clinical trial. But the COVID-19 pandemic struck soon after, making enrollment unfeasible.

In May 2024, after a four-year hiatus, Dr. Molfenter and her team resumed their quest. “When I talk to trainees, I tell them this is a story of not giving up,” she says. “We trusted in our own abilities, stuck it out, and here we are.”

Sending Swallowing Muscles to Boot Camp

In the new study, the team is investigating the effectiveness of a 12-week course of swallowing exercises, with or without daily protein drinks, to improve the composition, force, and physiology of the pharyngeal muscles as well as participants’ overall health and physical function. The researchers plan to follow 80 community-dwelling older adults for six months each over a five-year period.

“We think of it as a boot camp for swallowing muscles,” Dr. Molfenter says. “Our goal is to see whether a regimen of workouts and protein supplementation can rebuild those muscles in aging adults, just as it does for other muscles in people who go to the gym.”

Participants must be 65 or over and score as pre-frail on standard diagnostic tests. They act as their own controls for 12 weeks before being randomized to complete swallowing exercises alone or with dietary supplements. Both groups complete a battery of exercises (such as effortful saliva swallows and tongue-hold swallows), with the number of sets increasing as tolerance builds. Those in the supplement group also consume a bottle of protein drink each day throughout the intervention period. Those in the control group consume water in equal amounts.

“As we’ve seen with other types of resistance training, people who are physically stronger tend to be more resilient when faced with health challenges.”

At baseline, week 13, and week 28, participants undergo a variety of tests. The thickness of their pharyngeal muscles is measured using MRI, the biomechanics of those muscles during swallowing is assessed via videofluoroscopy, and their force-generating capacity is gauged through high-resolution pharyngeal manometry. Participants are also scored on gait speed, balance, and standing from a seated position to assess overall physical health. Their levels of fat-free muscle and pre-albumin (a marker of undernutrition) are quantified.

“This is very much a multidisciplinary study,” Dr. Molfenter notes. Her collaborators include Milan R. Amin, MD, director of the NYU Langone Voice Center, speech pathologist Matina Balou, PhD, radiologist Mari Hagiwara, MD, and Kathleen Woolf, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Nutrition and Food Studies at NYU Steinhardt.

Envisioning Clinical Applications

If the trial shows positive results, Dr. Molfenter suggests, the next step could be to test pharyngeal strength training in a range of clinical settings—from community centers to senior living facilities.

“Building up the swallowing muscles could protect older adults from developing dysphagia if they have a stroke or develop Parkinson’s disease or cancer of the head and neck,” she says. “As we’ve seen with other types of resistance training, people who are physically stronger tend to be more resilient when faced with health challenges.”